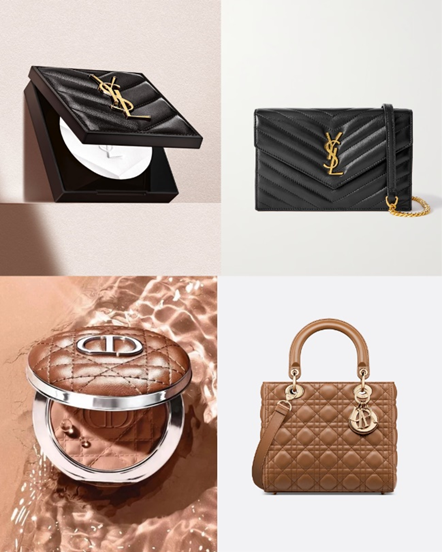

Image credit: Dior

With handbags now past €5,000, luxury has quietly priced out its own believers. The entry ticket to aspiration has vanished.

Luxury houses have crossed a value frontier—alienating first the aspirational, then even the comfortable upper-middle clients who once bought a bag at €2,000–€3,000 without hesitation but now think twice when the same bag costs double.

In this climate of alienation—analysts call it greedflation—beauty has evolved from secondary category to strategic bridge. It has become the visual echo of hard luxury: a form of access that keeps consumers participate in the dream without crossing the five-figure line.

Design continuity keeps clients emotionally tethered when prices push them out of handbags or even small leather goods.

Beauty once democratized luxury; now it defends it. The packaging keeps the house code alive.

“The Cannage stitch on the compact powder doesn’t sell foundation; it became the foundation.”

For decades, perfume and make-up were the entry ticket into luxury—small indulgences that carried a logo, a scent, a touch of belonging. But as handbags moved beyond reach, the hierarchy flipped. Beauty didn’t just complement hard luxury; it replaced it.

Today’s compact is designed like a mini bag: metal clasps, quilted leather, signature engravings. The houses disguise make-up in leather to keep us in the loop—to give us the illusion of owning what we can no longer afford.

Image credit: YSL.com and Dior.com

The illusion works—but only if the math does. Beauty must be expensive enough to dream, close enough to buy.

Some houses have perfected this equilibrium. YSL Beauty generated around €2.9 billion in 2024, nearly matching Saint Laurent’s fashion and leather division. Chanel Fragrance & Beauty is estimated at $7–8 billion—roughly 40 % of total group sales.

Even younger labels have used beauty as a turnaround strategy.

When Victoria Beckham launched her beauty line in 2019, it wasn’t an accessory—it was a lifeline. The move anchored her brand in recurring revenue and modern relevance. Today, Victoria Beckham Beauty drives over 20 % of group turnover. Priced around $60, it struck the ideal frontier: premium enough to feel luxurious, attainable enough to convert. Authenticity became the branding; price, design, and narrative turned credibility into conversion. The brand now sells one eyeliner every 30 seconds.

These figures show why beauty stabilizes a brand’s P&L—fast cycles, recurring consumption, low CapEx—if pricing and identity stay coherent.

YSL, Dior, and Chanel hit that sweet spot: affordable for aspirational shoppers, credible for HNWIs. Others, testing the upper edge of pricing power, are discovering its limits.

Push accessibility too far and the bridge becomes a wall.

Louis Vuitton’s $160 lipstick isn’t a gateway—it’s a token for existing clients. Sold only in LV stores, it targets shoppers already buying boots or bags, not newcomers seeking entry. For new buyers, a $285 cardholder feels like ownership; a $260 eyeshadow does not.

Even Hermès misread the price elasticity of desire: beauty sales fell 5 % while group revenue rose 9 %.

Refillable compacts and metal packaging now mimic the permanence of handbags, reframing disposables as forever objects while aligning with sustainability narratives.

But when beauty becomes too rarefied, it stops being a bridge and turns into a barrier.

“When the volume engine starts behaving like the handbag, the model breaks.”

At that point, beauty stops being a cash cow and becomes a showroom. Growth stalls, accessibility vanishes, and the entry-ticket logic collapses.

Louis Vuitton and Hermès now flirt with that threshold—prestige intact but scalability strained.

Hermès runs roughly 40 % operating margin, LVMH’s Fashion & Leather Goods 38 %, while L’Oréal Luxe (YSL Beauty) 21 %. That gap explains why beauty must stay volume-driven: the win lies in velocity, not margin.

Beauty as “affordable luxury” is itself an illusion—and Kering ‘s new CEO understood that. The €4 billion sale of the beauty division (including Creed) to L’Oréal wasn’t an exit; it was a re-armament. The deal freed cash to refocus on core houses and created a joint platform to scale beauty under a lighter structure.

L’Oréal handles manufacturing, marketing, and rollout for Gucci, Balenciaga, and Bottega Veneta; Kering retains creative control and brand equity. It’s an asset-light model: the volume specialist runs the engine, the luxury group collects the halo.

As CEO Luca de Meo put it:

“Saint Laurent Beauty today generates revenue equivalent to the fashion house. Imagine what Gucci Beauty could become.”

The global beauty market—projected near $590 billion by 2030—is luxury’s most resilient and most crowded arena.

Yes, beauty sustains visibility when core categories slow. But success depends on coherence. Price discipline, design integrity, and emotional storytelling decide whether a beauty line becomes a buffer or a blind spot.

Simply stamping a logo on a lipstick no longer works. Consumers know the about formulations, compare the value, and choose with precision.

A proof that desire, narrative, and brand power begin at the beauty counter, not on the runway.

Sources & Footnotes

Fashion Office

Fashion Office

Banyan Tree Alula, Saudi Arabia Gulf sovereigns are moving beyond capital deployment to cultural authorship —...

Fashion Office

Fashion Office

Why Luxury’s Next Big Price Move Will Make or Break Brands? Chanel Spring/Summer 2026 The luxury...

Fashion Office

Fashion Office

In June 2025, Hermès brought its equestrian heritage to Shanghai with the Au Galop! runway show—transporting...

No comments yet.